That could prove unsettling for investors if a new chair takes the helm next year and opts for a more ambitious approach to reducing the Fed’s big bond holdings.

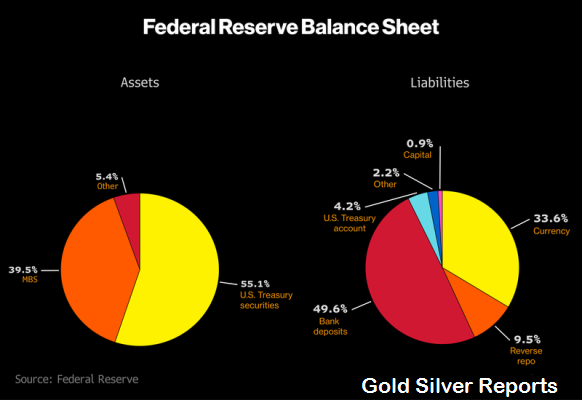

- 1 The Fed, which holds $2.5 trillion of Treasury debt and $1.8 trillion of mortgage-backed securities on its balance sheet, will discuss its strategy for reducing those stockpiles when it meets on June 13-14. The Federal Open Market Committee is also widely expected to lift interest rates for the second time this year.

Policy makers have said they will probably start a multi-year drive to shrink the central bank’s $4.5 trillion balance sheet later in 2017. Several though have suggested that they’ll defer judgment on how far they’ll go until after the draw-down has begun.

“We have not made a decision about the long-run framework, and we are not going to make one before the beginning of the normalization process,” Fed Governor Jerome Powell told the Economic Club of New York on June 1.

That’s not an inconsequential question. It could mean the difference between the bond market having to absorb $1 trillion or $2 trillion of debt securities thrown off by the Fed in the coming years, according to Michael Feroli, chief U.S. economist at JPMorgan Chase & Co.

The Fed, which holds $2.5 trillion of Treasury debt and $1.8 trillion of mortgage-backed securities on its balance sheet, will discuss its strategy for reducing those stockpiles when it meets on June 13-14. The Federal Open Market Committee is also widely expected to lift interest rates for the second time this year.

The ultimate size of the central bank’s balance sheet is bound up with the issue of how the Fed chooses to conduct monetary policy. And that in turn will depend on who’s in charge of the central bank after Yellen’s current term expires on Feb. 3.

President Donald Trump has yet to tip his hand on whom he’ll choose, though he’ll probably have to name someone months before Yellen’s tenure ends in order to give the Senate time to consider the nomination. Trump hasn’t ruled out giving Yellen a second four-year term.

Corridor vs Floor

The existing constellation of policy makers seems to prefer retaining the “floor” framework now in place for setting short-term interest rates. That methodology requires an elevated balance sheet to work and hinges heavily on the ability of the Fed to pay commercial banks interest on the reserves they hold at the central bank.

“Such an approach was seen as likely to be relatively simple and efficient to administer, relatively straightforward to communicate, and effective in enabling interest rate control across a wide range of circumstances,” according to a summary of FOMC participants’ views in the minutes of their Nov. 1-2 meeting.

If instead the Fed returned to the technique it used prior to the crisis, the balance sheet could be much smaller. That’s because the “corridor” framework was predicated on keeping reserves to a minimum. The Fed then managed the federal funds rate through frequent open-market operations as it sought to match the supply of reserves to demand from commercial banks.

That’s the approach favored by Stanford University professor and potential Fed chair candidate John Taylor. He argues that such a strategy would reduce the Fed’s footprint in financial markets and so give market forces a greater say in determining rates.

“The main criterion for the size of the balance sheet is that the supply of reserves should be in a range where the supply and demand determines the interest rate in the market,” Taylor said in an email.

He contends that a smaller balance sheet would leave the Fed less vulnerable to political pressure to buy debt to help out the federal government. It also might dampen congressional criticism of the Fed for paying commercial banks money on the large amount of reserves they now hold at the central bank.

Two other potential Fed chair candidates, Dartmouth College’s Peter Fisher and the Hoover Institution’s Kevin Warsh, have also called for the central bank to downsize its balance sheet, though they declined to say if they’d go as far as Taylor.

The Stanford economist suggested the balance sheet might end up at “somewhat more than $2 trillion” after normalization is complete.

That’s below the $3.1 trillion level primary dealers predicted it would reach at the end of 2025 in a survey by the New York Fed conducted in April.

“The market cannot simply assume the path indicated by the current FOMC will necessarily prevail over time,” Krishna Guha, vice chairman of Evercore ISI, said in an email. “That includes putting some weight on scenarios in which the Fed under new leadership adopts a more aggressive balance-sheet normalization path than the Yellen Fed is indicating.”